Creating a care-share team from within your safety net requires you—at some point—to ask for help. We call this a help appeal. We first learned of help appeal in Zurich, Switzerland, at a lecture given by the author, Dr. John Gibson, and attended by Dr. Albert Wettstein, Switzerland’s director of Public Health. Afterward, Dr. Wettstein explained to John that the Swiss, particularly men, are very private and self-reliant, and dreadfully bad about communicating a medical or life problem. Dr. Wettstein said, “I invented help appeal for us Swiss so we could deal much better with illness.” According to Dr. Wettstein, developing help appeal was quite simple. He created sample letters and telephone-call scripts that instructed people how to explain an illness to friends and relatives. Those letters and call scripts became the help appeal that these men (and sometimes women) used to tell their friends and relatives about an illness, disability, disease, or extensive and frightening medical test. With a simple script in hand, the men found it much easier to ask for help. We’ve found that a similar approach can be equally well applied when facing other life changes and challenges.

Dr. Wettstein added, “You Americans have ‘sex appeal.’ I watch your TV and see how sex appeal is used to sell everything. Now we Swiss have ‘help appeal.’”

Jim’s Help-Appeal Phone Call

“Hello,” Jim said over the phone to his old friend Fred. “I have something important to tell you. Do you have a couple of minutes? I’ve just come back from a follow-up visit to my doctor, where I was told, based on the biopsy, that I have prostate cancer. I don’t yet know what this will mean for me. I may be cured, maybe not; it may require a lot and be a long ordeal, maybe not. I will find out more in the coming weeks. In the meantime, I wanted you to know. I don’t know how you can help me during this time, but just knowing that you are there is helpful to me. I’ll keep you posted as I learn more about my cancer and what I have to do. Oh, you should also know that I am not restricted in any of my activities, so we can still go on our Saturday morning walk around the lake and have breakfast afterward.”

Jim’s example may help you think about drafting your own script. If you have invited others to join you in creating a safety net or forming a care-share team for yourself or someone else, we’d love for you to tell us about it: Go to the Personal Invitation to Readers in the back of the book to find out how. By sharing your experience you will help us create what we hope will be a second book of examples that will serve as encouragement and support for others. You’ll be part of creating a written safety net for future readers.

In our years of working with care-share teams, we’ve discovered many simple, effective ways to ask for help; there’s no one way that’s right for everyone. In the following stories, Sarah, Lisa, Mary, and Sid preferred face-to-face requests and letters to communicate, while Ted and Sue used e-mail and phone calls.

Sarah’s Dilemma: Home or Nursing Home?

Sarah, an independent and widowed 71-year-old woman, knew it would be hard to ask for aid after her hip replacement surgery. She also knew that if she didn’t have help, she would be forced to spend extra days in a rehabilitation center or nursing home. And she would have to pay for a 24-hour caregiver until she could get around her house, and then for more days, maybe weeks, until she could drive, grocery shop, and go back to her normal life.

Sarah made some notes to herself on how she would express her help appeal to her good friends. With notes completed and words rehearsed, she mustered up her courage and invited her five best friends for a potluck dinner at her house. So that she wouldn’t back out at the last minute, she told them that she had something important to say.

When the evening came, Sarah sat down with her friends and began with a simple explanation: “You all are my best friends and I know you have busy lives. I need to have hip replacement surgery, and I’m not sure what all my recovery will entail, but I know I will need help.” One of Sarah’s younger friends immediately jumped in, “Oh, my aunt went through that and the whole family helped her. We’ll be your family. I’ll make a list of things you may need. I’ll ask my aunt, and we can make a schedule.” Another friend offered, “And I can come and sleep here, I’m retired. Laurence [her husband] won’t mind, and we can eat popcorn, watch sappy videos, and before you know it you’ll be up and around.”

Sarah’s friends showed that they cared about her in a way that she had not anticipated, and that deeply touched her. These friends, and a few others, instantly formed the care-share team for Sarah that allowed her to go home. This incredibly kind act not only relieved Sarah, but also enriched the lives of all of her friends, who, in turn, became closer to one another.

Ted’s E-mail to Warren’s High-Tech Work Group

I think all of you know by now that Warren has cancer. There’s no cure for it, and the doctors don’t give him much of a chance for living through the year.

Doesn’t get any tougher. Warren, his wife, Carolyn, and their eight year old will need our help. I watched a cousin go through this a couple of years ago and it’s brutal.

Warren and I are close. I’ve talked with Carolyn, and they’re open to help. I’ll be lead on this one. Same rules: Don’t take on anything you don’t think you can do. Communicate, communicate, communicate.

More e-mails shortly. – Ted

His work group’s responsiveness pleased Ted. Not everyone could actively participate in the team, but Ted knew that Warren would feel really good about receiving so many expressions of concern.

Ten-year-old Lisa took a straightforward tact in asking for exactly what she needed.

Lisa’s Letter to Her Fourth-Grade Classmates

Hi Everybody,

Thank you for your get-well cards. My doctor says I am getting better fast even though the car wreck was just three days ago. I miss all of you and Miss Brown, too. The doctor doesn’t know when I’ll be able to go home and back to school. I don’t want to get way behind in my classes and maybe fail. Will you help me?

Here is what I know I need now: Miss Brown’s notes and assignments for all my classes. Please pick up my library book so I can start my book report. Pick up a video and watch it with me. And visit me on Sunday because my family has to go to Grandma’s for her birthday.

Thank you, Lisa

Some situations are far more complicated than Lisa’s. When you’re faced with a long-term illness or difficult diagnosis, sometimes the only thing you’re certain of is that you need help. You may need to gather your team together to figure out how to proceed. That worked well for Tom and Sue in the next story.

Sue Steps In

Tom found out that the symptoms he’d been experiencing were due to an advanced cancer. Overwhelmed at the thought of a foreshortened life, he fell into a deep depression that threatened to flood his partner. Sue, however, had had some experience with illness in her family and decided to reach out on Tom’s behalf. Calling on Tom’s sister and brother and a cadre of friends, she outlined his diagnosis, the course that they expected him to take, and both of their needs. Most of those contacted were ready to help immediately. Sue set up an initial meeting to define some roles and expectations, and Tom found himself surrounded by loving, caring team members who stood by them during his treatments.

In yet another case of someone seeking help for a spouse, Mary reached out by letter to the couple’s church group. Not knowing what might be needed or helpful, Mary simply explained Sid’s situation. The responses became the inspiration she needed to later mold a care-share team.

Mary and Sid’s Letter to Their Congregation

Dear Friends,

As some of you may know, Sid suffered a major stroke six days ago. The doctors won’t say how much he will recover. He will start speech and physical therapy in the coming weeks. We both missed attending church last Sunday and sharing the fellowship of your company.

Sid and I don’t know what the coming weeks and months will bring, but we ask you, our friends of many years, to hold us in your prayers, along with the many others who also need your prayers.

Sid has been home for two days, and we’re realizing how different our lives will be for the foreseeable future. We don’t know yet what help we will need, and we know that many of you are already over committed and over extended. We would absolutely not want to add more to your load, but I can imagine that some assistance would make a big difference in our lives.

Sincerely, Mary and Sid

As Dr. Wettstein had identified for Swiss men, the value was in the asking and receiving, which is true for all of us. We want to help you integrate the help-appeal concept into your life. We want to help you understand the power of sharing in the care of others. We build and strengthen our personal community through asking for and giving help. This is a radical shift in the definition of strength. We suggest that strength lies in taking control through asking, delegating, and getting ready.

Practice Will Help

It’s often not easy to ask for help. The internal muscles required for doing so don’t get much exercise in our culture: It takes practice. You can start laying the groundwork for reaching out. Solely for the practice, you can invite neighbors to a potluck, ask for directions, call a friend to join you for a movie, or ask others to join you in forming a volunteer group to support someone else. The important part is to begin practicing both asking for help and giving it.

Any of these activities, especially if they’re unfamiliar, will gently stretch your capacity to reach out. Some version of the words “Is it okay if I ask you for help?” is almost always met with willingness. Even if the person can’t do what you had hoped, you’ve opened a door. And each opening will make it easier to talk about things that are scary or make you feel vulnerable. Getting comfortable asking with relatively simple and small requests is a powerful step toward preparing yourself to ask in a life-changing event. Besides being culturally conditioned to be independent, we face other barriers that keep us from disclosing our needs and requesting assistance.

Barriers to Asking for Help

Some common barriers that often get in the way of asking for help include these questions and fears:

- “What if they say no?” (a fear factor)

- “I can’t ask: In our family we take care of our own.” (a pride factor)

- “I don’t want to be ‘beholden’ to anyone.” (a self-worth question)

- “I can take care of myself.” (an individualist myth)

- “If I ask for help, I’ll look weak.” (another pride factor)

- “If they really knew me, they’d reject me.” (another self-worth question)

Yet, the very same people who voice these fears often describe how good they felt when they’ve helped a friend or family member. They also admit that giving help and interacting with others while doing so deepens their relationships. Deep down, they know that good things often come from both helping and being helped. In times of stress and need, however, fears and questions can get in the way.

Granted, asking for help is a risk, but many of the best things in life only come when we reach out and take some risks. Even when you do risk asking for help, there may be times when you don’t want to accept the sort of assistance that is offered. In fact, you may have very good reasons for rejecting someone’s offer. John was surprised when Peter initially declined his offer, as he tells in this story.

If I Ask, Can I Trust You to Say No?

My neighbor, Peter, recently was diagnosed with cancer. He needed radiation treatments daily. When I found out I asked, “Peter, can I help you move in and out of your wheelchair, take you to your radiation treatments, and help you with any personal physical issues?” He smiled, “John, thanks. I would agree, but you know that I am not sure I can trust you.” I was stunned and asked what he meant. He said, “I would only feel free to ask you to help me if I felt confident you would say no if you had something else you really needed to do.” His eyes locked into mine and I realized he couldn’t be more serious.

As was his way, he sat quietly and patiently while I collected myself. When he saw I was ready to respond he added, “I have had several people sign up to help me. With a couple of them, like you, I’ve wanted reassurance that they could say no if they needed to. Some couldn’t or wouldn’t say no when they needed to and it became awkward for both of us. I want you to know that I value your offer, but I am worried that it will affect our relationship.”

Peter gave me permission to say no, whenever and without guilt. What a gift! When I promised to say no if I needed to, he knew I meant it. He smiled and said, “I’ll put you on my list!” He felt better once he’d gotten over his worry about me. Eventually during my time with him, I occasionally had to say no. Peter laughed each time and said, “So I can trust you, can I! Well, good! Thanks, buddy, for all you’ve done, and I’ll call again soon.”

John learned a valuable lesson from his friend: It’s important to keep personal commitments and needs in mind when extending help.

Barriers to Saying “I’ll Help”

As shown in John’s story above, there can be reasons why someone might not be an appropriate person to ask for help. The story also illustrates why someone might be reluctant to offer. We have observed many barriers to saying yes to an appeal for help. Some of the more common barriers include these:

- “What if they ask me to give more than I can right now?” (a question of being able to set limits or boundaries)

- “I won’t be able to cut back on or stop helping when I need to.” (a fear of being overwhelmed)

- “I can’t intrude.” (a belief about privacy)

- “This is a family matter. They should handle it themselves.” (a myth about independence)

- “I’m uncomfortable around sick people.” (a fear of discomfort)

- “My life is already too full.” (another fear of being overwhelmed)

Analyze—and perhaps challenge—your fears or concerns. At least start by gathering more information. Look for small ways you can help. In most settings you can discuss concerns and constraints on your availability with the person asking for help. You may not be accustomed to having this sort of open and honest personal discussion. However, we believe in our increasingly complex world, with increased life expectancy and accompanying periods of illness or disability, we all need to practice and get better at these sorts of conversations. The point is to offer what you can freely give, as Rosa does in this story.

Rosa’s Telephone Message to Patricia before Her First Chemo

Hi Patricia, this is Rosa. I know this afternoon is your first chemotherapy. I have been saying prayers for you. I have asked the spirits of my ancestors, guardian angels, and our heavenly father to guide your treatment to the very best outcome. I pray that your heart will swell with the love all of us send to you, make you stronger, and channel the medicines to just where they are needed. We go with you on this day as we will always go with you, but we send a little extra love this morning and throughout the day.

Patricia, we all love you.

It’s Hard to Ask

Most people prefer not to have to ask for help. A few recoil at the very idea and can’t even imagine asking. For a few it’s easy. In between are the many for whom it’s difficult or for whom the preceding barriers get in the way, but who determine to go ahead anyway. Learning how to ask for, accept, and offer support is an essential life skill. Asking for help can be an act of love and protectiveness toward those who are loved. Receiving it can be a gift to the giver. The next story tells a little bit of one couple who really understood this.

Alfonso’s Help Appeal: Update E-mail to His Team

Alfonso, the pillar of good health, was diagnosed with cancer. He and wife, Lana—through phone calls, in-person conversations, and e-mail messages—notified friends and relatives of his diagnosis. Lana regularly sent out e-mails letting their friends and family know how Alfonso was doing. The latest e-mail described his upcoming chemotherapy and asked that all hold him warmly in their hearts and in their prayers.

You can become comfortable with asking for help. With time and practice, you will be able to ask in a calm, easy manner and to receive responses in a levelheaded and thoughtful way. It’s not easy to respond calmly in the midst of an illness, injury, or major life change, so try practicing and preparing now. Use small opportunities to practice, learn, and grow in this area. If you do, it’s likely that, like Marty and Olie in their stories below, you’ll be ready if there’s a need. Or, like Jeff, you’ll at least be ready to begin thinking about it.

Marty’s Letter to the Firm’s Partners

Well everyone,

I shouldn’t have believed you all when you said I was too mean to ever get sick. Just can’t trust you—us—lawyers.

Your cards, flowers, and visits have been wonderful. Never thought I’d need a family, although I made a couple of stabs at marriage. Seems you all have become my family in the last twelve years since Molly and I ended it. With my life it was just a matter of time until I’d need some sort of safety net.

The doctors say my heart attack was a whopper, and I’ll need more procedures to even regain 40 percent functioning. My counselor says I need a care-share team, and he understands that there are a lot of friends and colleagues who care about me. (Little does he know that you all just put up with me.)

Anyway, with his help I am holding a meeting—noon, next Wednesday in the large conference room—to try to begin organizing the personal and professional help I’ll need during the next few months.

Show up at your own risk. We’re bringing great sandwiches from Zabar’s. No commitment required. Brainstorming only.

Love you all, Marty

Olie’s E-mail: Important Changes in My Life

Dear friends,

I am writing to inform you of an important change in my life. As some of you already know, a few weeks ago Collette and I separated. At the moment, we are working through the divorce process. For me, this has been a tough choice, but necessary for my future. Collette was hurt at first, but not completely surprised. During the past few weeks I’ve found that letting people know about this major change helps me quite a bit emotionally, so I thought I’d reach out with an e-mail, even to those friends who are physically far away. You may do whatever you want with this information.

What will happen in the short term? Right now, Collette and I are finalizing the divorce agreement. In all likelihood it will be another five to six months before everything is finalized. I want to reassure you that during this time Collette has complete access to health insurance through my employer, as well as exclusive use of our car and our condo in Bellevue. What will happen in the long term? I will let Collette tell you about her own plans for the future, if she chooses to do so, but for the next year and a half, I will be busy working and finishing my PhD. After that I will continue working as a researcher at the University of Washington.

What can you do? I don’t need anything in particular from you, even though a phone call or an e-mail is always welcome. The only thing I ask is that those of you who are good friends with both Collette and me continue to be friends with both of us. I am doing very well. My parents have helped me enormously in these tough weeks, and I am now happily independent. Collette will probably need more help, not so much emotional, but practical. Because I don’t want to presume to know her needs, I will let her express them to you, if she wants to.

Thanks for caring, Olie

Jeff’s Waiting-Room Thoughts

Jeff was sitting in the lobby of a well-known cancer center, waiting for his appointment. Except for some minor surgeries, he had always been the healthy person and the one providing the help. This waiting room felt totally foreign to him.

He watched as one elderly gentleman carefully tended to his wheelchair-bound wife, while another nearby couple seemed worlds apart: Hubby was sitting a distance away from his wife, who sat blankly, a hat covering her hairless head. If Jeff hadn’t seen the two of them enter the office together, he would have thought them strangers to each other.

“What would my experience be like?” he wondered. Would my family reject me or become distant? Would I share the intimacy of the first couple with my wife?” Then he remembered a book he had read years before, Counting on Kindness by Wendy Lustbader. He thought about many friends he had assisted on journeys into and through illness. He wondered how it would be now that he was the one facing cancer. He felt fortunate he hadn’t had to ask for much help thus far in life. Slowly, it occurred to him that he would need to ask for help. He didn’t know how to do it, but he came from a long line of survivors, and if help was needed he’d somehow ask for and get it.

Friends and Relatives Respond to Help Appeal

If you have a friend who is feeling out of control and uncomfortable just asking for help—how will you respond? Instead of simply asking, “Is there anything I can do?” consider offering more: “Can you think of anything right now that I might do?” or “May I call you in the next few days to see how you’re doing and to again ask how I might help?” or “If you think of anything I might do, or if you just want to talk, or if you just want to spend time together and not even talk about any of this, will you please pick up the phone, dial my number, and let me know?” Each of these offers leaves room for the person who seems to be in need to think about what might be helpful, to take control, and to give a more thoughtful reply.

In the following example, Steve calls back his friend Mark, who had left a message about his medical diagnosis.

Steve’s Voice-Mail Offer to Help

Mark, we got your message on Sunday. I’m sorry I haven’t called back sooner. It kind of hit me just like a punch in the stomach when you were describing the diagnosis. I felt a mixture of anger at the disease and love and care for you and Sylvi, but then I’m sure you’re going through ten-fold beyond what I can imagine.

But just wanted to let you know we got the message. I’ve been thinking a lot about you and praying for your health, your good care, and good counsel from your medical advisors.

The most important thing to me right now is that once your treatment regimen becomes clear, I really hope I can be a part of that team that will hopefully help you defeat the disease. I really want to play a role for you, Mark, in that battle. Please know that we’ll be there, whatever it takes.

Again, our thoughts and prayers are with you, Sylvi, and the boys.

Mariah is someone else who was surprised with a scary diagnosis. At age twenty-eight, her liver was dying. When this was diagnosed as a genetic disorder, primary sclerosing cholangitis, she and her husband, Tom, knew they had to look beyond family members for help. They established a Web site through www.caringbridge.com and used it to notify friends, former co-workers, and church members of the situation, to ask for help, and to keep all of them up to date. Here are some responses to Mariah’s Web site.

E-mail Messages Responding to Mariah’s Help Appeal

Dear Mariah,

I have been keeping up with you on your Web site. I just want you to know that I think of you often . . . and I am hoping you get out of the hospital soon. Please let me know if there is anything I can do to help with you or Jonah. Emily misses him; she does not understand why he is not in school with her. Please know that you are in my thoughts and prayers.

– Ann

Dear Mariah and Tom,

Let us know what we can do for you this weekend, if anything. If you need me to bring you home, I’ll be happy to do so. If you need us to keep Jonah while Tom brings you home, we’ll do that, too. I am happy to see your numbers coming down. Let’s hope they stay there now that the duct is no longer blocked. I didn’t call last night because I didn’t want to wake you, but I’ll try to call tonight.

Love, Dad

Hi Mariah,

I hope you are feeling better. I am so sorry to read that you had to go back to Georgetown again. Please let me now if there is anything I can do, especially now that Tom has gone back to work. I know you have neighbors, but I am not that far away. Michael, my older son, started school this past Monday and Sam starts preschool next week. Best of luck to Jonah on his first day of school. Michael started third grade this year, and I still cried when he got on the school bus. It is so hard to let go. My prayers are with you. You are such an inspiration to me.

Lots of love, Josephine

Hi again Mariah,

My voice is a little odd (I saw my own ENT on Friday), but I can talk. So if you are bored don’t hesitate to call. Hang in there. I hope the doctors come up with some kind of idea for kicking this resistant infection for good. Big hugs! You are always in my thoughts, and I’m rooting for Jonah to have a wonderful kindergarten orientation!

Love, Patrice

Mariah,

It has been a very long time since high school. I have been busy myself battling cancer, but prayer goes a long way. I have had you and your family in my thoughts since you have been sick. Never give up hope, stay strong. You will be in my prayers.

– Yolanda

From the above examples, it’s clear that not everyone who is asked to help will actually want to or be able to follow through. If you’re the one doing the asking it’s important to not take this personally. Everyone in your circle has her own circumstances and personal history that will affect her capacity to say yes to your invitation. This was true for some of Mariah’s family and friends, and also true for Charles. After a car accident, Charles asked for help for his wife, Mary, who had suffered dreadful injuries and expected a long recovery.

Jenny and Ray Respond

Hi Mary and Charles,

This is Jenny. Ray and I were so saddened to hear about the terrible car accident.

We pray for a rapid recovery for all five of you. We understand that Mary will need several surgeries, and we especially pray for her.

Ray and I would like to be a part of the care-share team you mentioned in your letter. My 93-year-old mom back in Atlanta, however, is sick, and Ray and I are going back to stay with her. We hope to convince her to move out here. As soon as we get back next week, we’ll get in touch and help out. We’ll pray for all of you. Bye for now.

Unlike Mariah and Tom, who liked using e-mail, some people, such as Glenn in the example below, prefer face-to-face interaction when bringing important news. Glenn took a very public risk, inviting fellow members of his Rotary group to help when he needed it.

Glenn’s Invitation and the Response

“This is really serious,” Glenn said, addressing his Rotary group. “This is really serious,” he repeated. With voice faltering, he began, “I have just been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and my odds aren’t good. I joined this Rotary eight years ago to help others, and now I’m going to need help. I hope I’m not shocking you all too much, but you’re my friends and I wanted you to know.”

Following Glenn’s moving help appeal, Howard, the former Rotary president, stood up and spoke. With heartfelt emotion, Howard expressed his concern for Glenn and that he knew he was speaking for all the men and women present: “We will be there for you. If there is anything we can do to help, however small or large, we want to know. You’ve given so much to others and we’re happy to give back to you. Please keep us updated on your progress and your needs.”

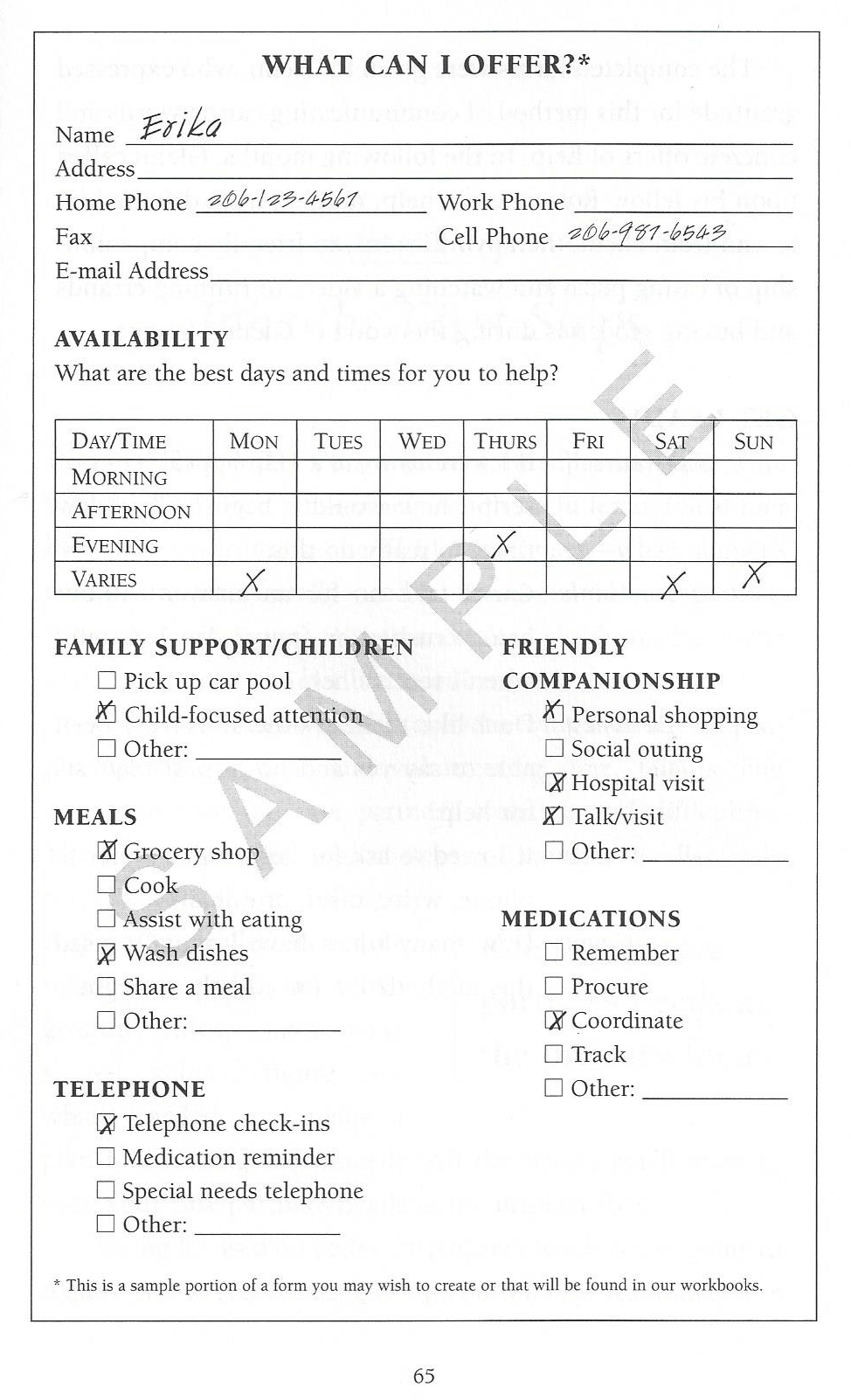

A few weeks later, a fellow Rotary member distributed copies of a form “What Can I Offer?” to each member to complete. Here is a sample segment of this form from our workbook.

The completed forms were given to Glenn, who expressed gratitude for this method of communicating caring words and concrete offers of help. In the following months, Glenn called upon his fellow Rotarians for help, ranging from driving him to and from chemotherapy infusions, to friendly companionship of eating pizza and watching a video, to running errands and buying groceries during the worst of Glenn’s fatigue.

Get Ready

Ask yourself: If I were to write a help-appeal letter or script, how would it begin? (Try a few times to really do this.)

Think: Can I take no for an answer without being crushed or angry? Am I grateful when I receive help?

Be honest: Do I like to help others? Have I been able to say yes and no to past requests for help?

Decide: If I need to ask for help, will I prefer to phone, write, meet, or e-mail?

Count: How many times have I actually used this method? Do I need help to begin?